Progressing towards TB elimination in South Korea: What’s next?

- March 28, 2023

- Evelyn Lee

- Posted in education

Progressing towards TB elimination in South Korea: What’s next?

Thanks to strong TB support policies and surveillance programs in South Korea, the total number of patients (new patients and retreatments) has steadily decreased by an average of 7.8% per year since the peak in 2011.1

TB cases in South Korea decreased from 65.9 cases per 100,000 population in 2018 to 40.3 cases per 100,000 population in 2022.1 This is the lowest TB incidence rate the country has achieved to date.

Despite this achievement, South Korea still has the highest TB incidence rate among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries and the highest mortality rate among domestic infectious diseases, excluding COVID-19.

However, due to the impact of COVID-19, the global and OECD countries’ TB incidence rates have increased by 4.5% and 3.5% year-on-year, respectively.1

Excluding COVID-19, TB is still the leading infectious killer in South Korea, above carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) infection and AIDS.

Stepping up on latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) screening

In South Korea, since 2017, through significant funding, political will, and new diagnostics technologies, the government has attempted to close the gap in community transmission.

Through the implementation of mass LTBI screening of selected groups of people based on their occupation and living conditions, including daycare centres, students, healthcare workers, postnatal care workers, and the military, the country has achieved the lowest TB incidence rates in years – 40.3 new cases per 100,000 population.1

Under the updated Third Master TB Control Plan (under review), the country set a new bold goal of reducing the number of TB cases to 20 per 100,000 people in the next five years. The country can effectively reach the TB elimination phase, but what more does South Korea need to do to lower TB transmission?

Under this plan, the country has identified that preventing TB through LTBI control is essential to achieving this new target. The country is stepping up on LTBI control initiatives and executing programs that are based on the risk assessments categorised as follows:

| Sub-categories | Population | |

| At risk due to health factors | High-risk categorisation according to TB guidelines | People living with HIV Individuals who are taking or planning to take immunosuppressive medications for organ transplant; Individuals who are taking or plan to take TNF-α inhibitors; Those who have had healed TB lesions on a chest x-ray with no history of previous TB treatment Confirm TB infection in the last 2 years regardless of age. |

| Moderate risk categorisation according to TB guidelines | Silicosis Individuals who are using or plan to use steroids for an extended period; Chronic kidney failure; Diabetes; Individuals undergoing or planning to undergo head and neck cancer or sigmoid bypass surgery; | |

| Other risks | TB carriers; Seniors >65 years old; Excessive alcohol users, smokers and drug addicts; Mentally ill, liver disease (hepatitis) Malnutrition (underweight) etc. | |

| At risk based on working or living environment | Community facilities (Congregated settings) | Employees or inmates in facilities with high impact and risk of transmission in the event of a TB outbreak; Workers in medical institutions, maternity homes, schools, kindergartens, daycare centres and child welfare facilities (Article 11 if TB Prevention Act); Correctional facilities, nursing homes and facilities, homeless shelter residents, etc. |

| Vulnerable populations | Socio-economically disadvantaged groups with low access to healthcare for TB prevention and treatment, etc. Medicaid recipients, homeless, transients, etc Migrants from high-risk TB countries, undocumented immigrants etc. |

The plan acknowledges that screening blind spots remain, which are essentially those in the vulnerable population. More specifically, the plan addresses the issue of the lack of screening systems for LTBI, such as migrants from high-risk TB countries. However, the plan needs to address how to develop such a system that caters to this group of vulnerable populations.

Global migration and managing “imported TB”

Global migration is rising, brought about by various factors, including the need for skilled and unskilled migrants in certain countries. Migration of workers leads to more significant economic growth in the country or the region, and managing “imported TB” isn’t new.

For example, the number of new TB cases among foreigners in South Korea has decreased since introducing TB control policy for foreigners. This initiative included implementing mandatory TB screening for foreigners from countries when they are changing or extending their visas. This includes mandatory pre-departure active TB screening for work authorisation and residency permits from foreign nationals from 35 countries.

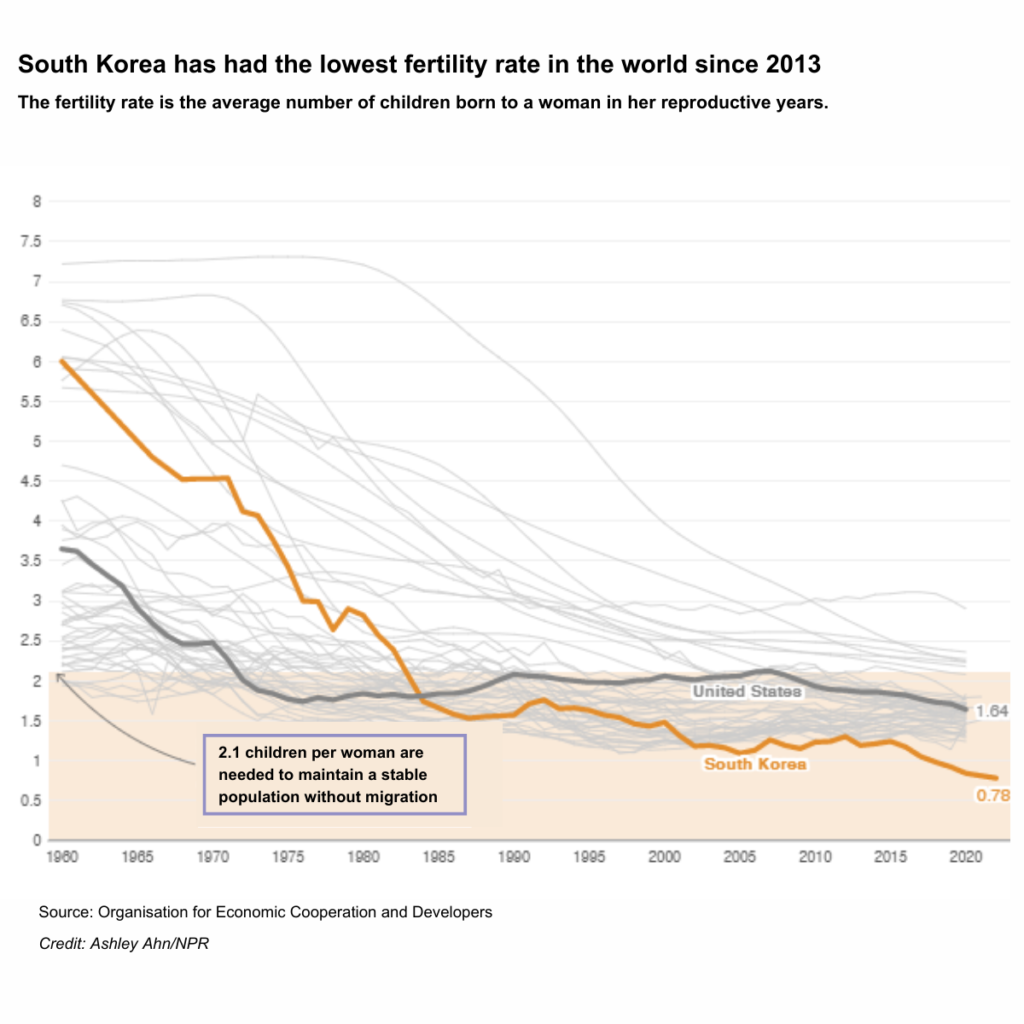

South Korea’s reliance on a foreign workforce is growing. Due to changing demographics, low fertility rates and many young South Koreans prefer white-collar, professional jobs; the foreign population doubled from 1.1 million to 2.5 million between 2009 – 2019.

This year, the government plans to bring in about 110,000 migrant workers to work in farms and factories, many of them from China, Vietnam, Mongolia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Uzbekistan. Many of these countries fall under high TB burden countries.

In 2018, the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency implemented a pilot LTBI screening for foreigners. The study found a higher LTBI prevalence among the immigrant population than the general Korean population. The LTBI infection rate was 28.5%, increasing with the length of stay. However, given that this pilot study tested the post-entry latent TB infection rate, it is difficult to determine if the infection occurred before or after the subjects entered Korea.

The study also recommended that this population be considered a priority need for LTBI screening and treatment, which aligns with WHO’s LTBI guideline recommendations.

To further strengthen South Korea’s TB control strategies among this vulnerable population group, extending LTBI testing to foreigners upon their arrival could be enacted.

Expanding LTBI screening closes the gap in community transmission

All public health interventions must consider cost and effect, including the long-term efficacy of treatment and care.

In a study in the UK to determine the cost-effectiveness of latent TB screening among immigrants, the study found that new entrants to the UK have a high prevalence of LTBI as they arrive primarily from countries with the highest burdens of TB. The study concluded that the cost of implementing LTBI screening using IGRA tests is cost-effective at a level of incidence that identifies most immigrants with LTBI. In addition, this approach will prevent substantial numbers of future cases of active TB.2

A recent study in Ireland – a low-incidence TB country — found that by not reaching the WHO End TB Strategy target between 2022 and 2035, the country will see 989 people having TB disease and 35 deaths; the cost of not meeting the End TB target is projected to be €70.779 million. Therefore, the study concluded that investment in effective interventions to reduce the burden of TB in Ireland is financially justifiable.3

The study also recommended expanding programmatic LTBI screening and treatment to include vulnerable populations, especially the marginalised, beyond those currently recommended for screening and treatment.3

In the absence of a new TB vaccine that is effective for adolescents and adults, screening and treatment of LTBI is the single most effective preventative measure.

Early detection and treatment of TB and latent TB infection amongst these vulnerable populations, including newcomers to South Korea, will lead to the interruption of TB transmission and reduction in community transmissions, ultimately strengthening the country’s overall public health system.

References

- 제3차 결핵관리종합계획(’23~’27)」 요약

- Pareek M, Watson JP, Ormerod LP, et al. Screening of immigrants in the UK for imported latent tuberculosis: a multicentre cohort study and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(6):435-444. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70069-X

- O’Connell, J., McNally, C., Stanistreet, D. et al. Ending tuberculosis: the cost of missing the World Health Organization target in a low-incidence country. Ir J Med Sci (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03150-3